Stories matter. Many stories matter.

Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize.

Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.

-Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, from The Danger of a Single Story

Mata Ortiz Pottery is without a doubt one of the most beautiful ceramic expressions in the world. With light walls and sinuous, geometric, painted designs, at its best the ceramic pieces are an ecstatic experience to behold.

This tradition started in the middle of the past century in the tiny village of Juan Mata Ortiz in northern Chihuahua, México, as a form of revival of the pottery from Casas Grandes – the culture that thrived in this part of the continent before the Spanish arrived. Over the course of fifty years Mata Ortiz Pottery became an outstanding artistic movement and one of the most relevant ceramic expressions in the world. It has remained vibrant and has continued to evolve into the new century.

But how did such a young pottery tradition emerge, seemingly from nowhere, and quickly evolve? The most popular narrative, the “single story” distilled from a larger, more complex narrative, involves only a few men. In the 1960s, the story of Mata Ortiz goes, these men developed the beautiful artistic expression that now encompasses more than four hundred potters and a whole community.

What follows is our history, the multi-layered narrative, as told by the people who have lived it.

BEFORE THERE WAS MATA ORTIZ THERE WAS ESTACIÓN PEARSON

BEFORE THERE WAS MATA ORTIZ THERE WAS ESTACIÓN PEARSON

The pottery village of Mata Ortiz was founded in 1909 as Estación Pearson, named after Frederick Stark Pearson, a brilliant American engineer, educated at Tufts University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His endeavors throughout the Western Hemisphere had considerable financial backing, and in México he obtained permits allowing his company, The México Northwestern Railroad Co. (Ferrocarriles del Noreste de México), to build an extension. The track that ran from Ciudad Juarez, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, to Nuevo Casas Grandes, approximately three hours southwest, would go farther south into Ciudad Madera, doubling the route’s length. Along the newly extended railroad, in the northern state of Chihuahua, México, the construction of what was possibly the largest lumber mill in North America began, established then as Estación Pearson. The rail line, finished in 1912, would help export lumber, extracted from the Sierra Madre and processed in the Pearson lumber mill, into the United States and from there to other parts of the world.

The civil war and the nationalization of the railroads during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) brought an end to several of Pearson’s entrepreneurial projects in the country. But his other interests, light and power companies in the United States, Brazil, and Spain, prospered. Pearson’s holdings grew. He electrified cities such as New York, Sao Paulo, and Barcelona until 1915 when Pearson and his wife, Mabel Ward Pearson, died on board the liner Lusitania, sunk by a torpedo launched by the German U-boat U20, while traveling to England. Meanwhile, the lumber mill had been working at a diminished capacity due to the civil war in México, and in 1921 it closed permanently. Then, in 1924, under the presidency of nationalist Plutarco Elias Calles, the name of the town changed to Juan Mata Ortiz, as did many others around the country to honor local or national “heroes.”

Juan Mata Ortiz was a major in the army of the state of Chihuahua. He was a participant in the not-so-publicized genocide against the Apaches and other Indigeous groups at the hands of both the Mexican and the United States armies in the border territories. The major was killed by Ju, one of the last Apache chiefs in the region. He ruled some of the Apache groups with Geronimo and other prominent chiefs at the time.1

And so, on October 13th of 1882, Mata Ortiz was captured and burned alive, thus dying a “hero” for the Mexican government, a few kilometers east of the village carrying his name today. Chief Ju died the next year. One of the versions of his death, though probably over romanticized, is that he was being chased by the Mexican soldiers when he blindfolded his horse to jump off a cliff so they wouldn’t capture him alive.

After the collapse of the lumber mill, the region’s workforce concentrated on railway repair – another early industry established in Estación Pearson. The railroad gave jobs to many citizens of Mata Ortiz, both directly and indirectly, as several other businesses were also established around the railroad. However, in 1955 the section of rail built by Pearson was purchased by the Ferrocarriles Chihuahua al Pacifico company and a few years later the repair workshops moved to the nearest city, Nuevo Casas Grandes. The people from Mata Ortiz were left unemployed and the businesses there, broken. To make things worse, the entire state of Chihuahua, historically plagued by drought, was going through a decade-long dry spell that severely damaged seasonal agricultural practices and the cattle industry. The combined loss of industry, which constituted the main income sources for the people of Mata Ortiz, was devastating.

Under this historic and social context, it is almost obvious that the inhabitants of Mata Ortiz would soon look for other means to support their families. Several of them reinvented themselves as purveyors of the archaeological artifacts contained in their families’ possessions, this included looting archaeological sites, digging for new “treasures” to be exchanged for food and clothes or a few pesos.

THE JOINT CASAS GRANDES EXPEDITION AND GEOGRAPHIC SITUATION OF JUAN MATA ORTIZ

THE JOINT CASAS GRANDES EXPEDITION AND GEOGRAPHIC SITUATION OF JUAN MATA ORTIZ

Almost concurrent with the aforementioned history a, what could be considered fortuitous, event happened for the people of Mata Ortiz. On May 29, 1958, the Amerind Foundation from Arizona and México’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH is the Spanish acronym) signed a treaty, The Joint Casas Grandes Expedition.4 This was a large-scale project devoted to the excavation and research of the archeological site of Paquimé, located adjacent to Casas Grandes, the modern town founded by Francisco de Ibarra in 1565. Casas Grandes took its name after the Spanish were told, by the “Indians" living in the vicinity, the old ruins were Paquimé which translates to Casas Grandes (Big Houses in English). The name is attributed to the substantial height of the pre-Columbian city ruins. The excavation project put under a magnifying glass the whole culture of Casas Grandes, including its soon-to-be-famous pottery. Special interest developed, not only from scholars in the archaeological and anthropological fields, but also in the black market. The ongoing research put archaeological objects into context and added value to the artifacts being sold for revenue to replace lost income streams.

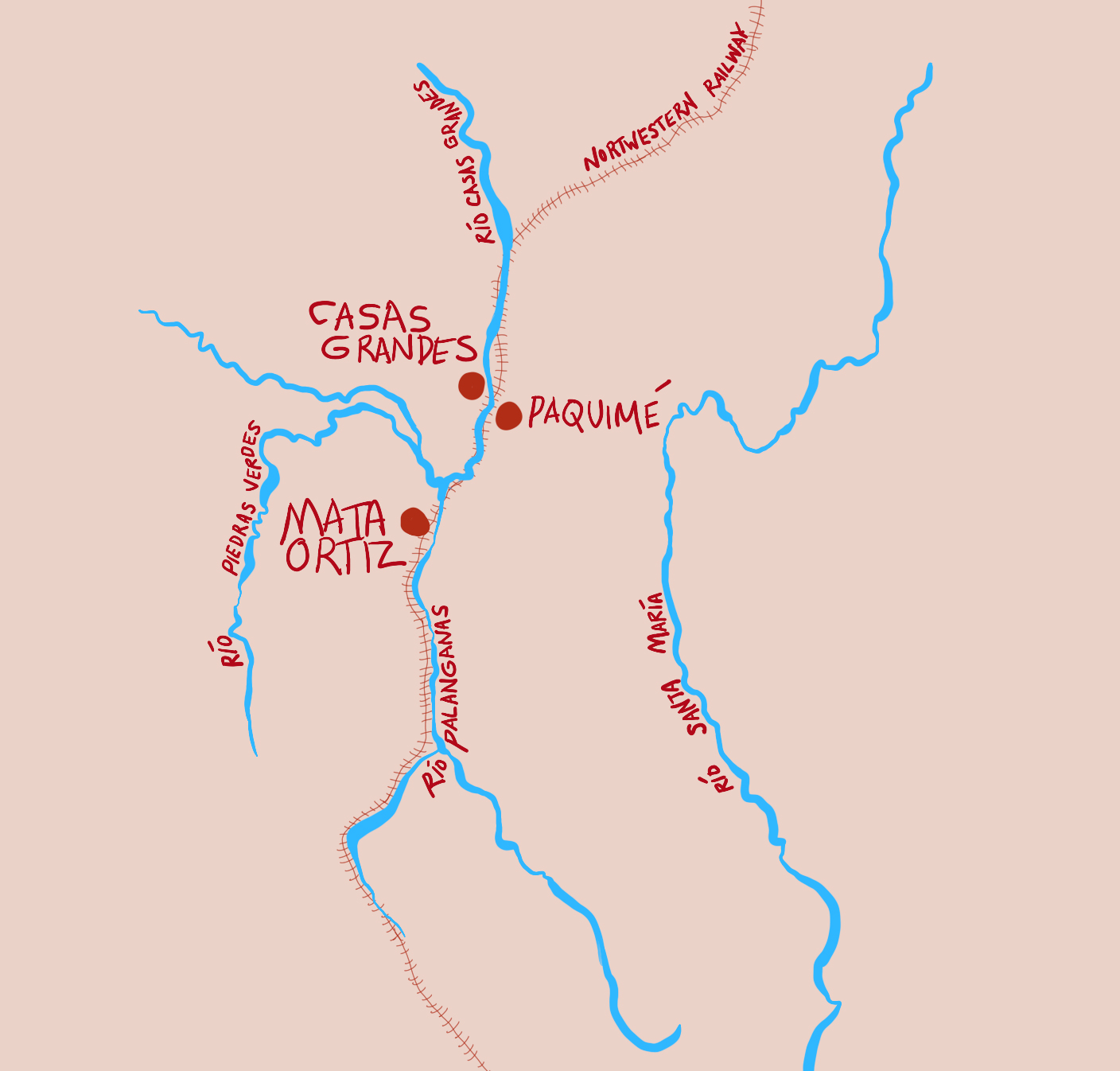

The Casas Grandes culture was established on the mesas and in the valleys of four rivers: Casas Grandes, Santa Maria, Del Carmen, and Bavispe. They run in the northwest of what is today the state of Chihuahua and northeast of the state of Sonora. Paquimé was the heart where the culture developed (approximately 900 – 1450 AD).5 Its influence extended throughout the continent. A trading network of cultural and material goods with the peoples of the Southwest and Mesoamerica, reached as far as the west coast by the Cortez Gulf. They exported ceramics and macaw feathers from birds they bred. Turquoise was imported from the Southwest and shells from the coast, distributing them in the north and Mesoamerica amongst other goods.

The Casas Grandes River is formed by two main tributaries coming down into the Casas Grandes Valley – the Piedras Verdes from the western mountains and the Palanganas River descending from the southern mountains – both belong to the Sierra Madre Occidental. Mata Ortiz is situated along the Palanganas River, some twenty-five kilometers south of Casas Grandes and Paquimé which, in turn, are situated along the Casas Grandes River. (See map for reference) And just as the old settlements were established along rivers and geographically strategic points around the valleys and mesas, so are modern towns – not only in Chihuahua, but all over México and the Americas.

The small city of Casas Grandes, in its modern state, is a good example of people occupying the same place over millennia, with sites containing evidence of continuous occupation since archaic times, such as El Convento site. In the same fashion Mata Ortiz, Santa Rosa, El Rucio, and the rest of villages along the railroad south to Ciudad Madera are built on top of ruins of villages from the Casas Grandes culture.

In many cases contemporary towns have been built using the remnants of the old buildings, mixing together soil, pottery sherds, and stone artifacts to make the new adobe structures, the favorite construction material in the region. The result is adobe buildings from the nineteenth and twentieth century in the Casas Grandes region show the weathered adobe bricks, pottery sherds, and arrowheads made on the site hundreds of years ago. Big metates (flat stones for grinding grains, cocoa beans, or plants) may be used in foundations and as cornerstones. In some cases the adobe even shows remnants of burials, such as human teeth and pieces of human bone. Less common, standing walls of rammed earth, a technique used to build Paquimé houses, were used as they were found and the modern rooms were completed with adobe. And so, since the foundation of Estación Pearson, now Juan Mata Ortiz or just Mata Ortiz as it is generally called these days, the people have known of the existence of a much older culture, now disappeared, whose vestiges could be found all around.

By simply walking over the hills and along the river mesas we can see the terraces built to farm the land more than a thousand years ago, as well as the mounds left by the fallen houses which we call montezumas. While the farming fields are being plowed or irrigation channels and foundations for houses are dug out, the turning of the soil shows all sorts of stone artifacts as well as pottery sherds, both plain and decorated. These latter artifacts are called pintas by the people in the region, the term referring to painted pots, or pintos when painted with human figures, also called monos.

OLDER PRACTICES WITH CLAY IN THE CASAS GRANDES REGION AND THE BEGINNING OF CONTEMPORARY MATA ORTIZ POTTERY

My assertion is that the quest to reproduce the pottery from Paquimé in the Casas Grandes and Mata Ortiz region did not start from a vacuum of knowledge, as has been repeatedly portrayed in the dominant narrative. Rather, the ceramic knowledge in our region comes from the collective understanding people within the aforementioned ethnic groups had about clay. The basic knowledge about the production of utilitarian clay objects, combined with social and economic contexts, played a major role in the rediscovery of methods and techniques used to make pottery from the Casas Grandes Culture. Moreover, contrary to the generally accepted or publicly spoken story, the information obtained through the observation of pre-Columbian pottery was acquired by looting, necessitated by the loss of industry. The compulsion to survive and provide for families put us in a position to study sherds found on the ground. From this struggle the Mata Ortiz pottery techniques were developed by the first group of enthusiasts led by Juan Quezada, Manuel Olivas, Emeterio Ortiz, Salvador Ortiz (not a brother of Emeterio), Rogelio Silveira, and some of their siblings. (Support for such an assertion follows in a future installment of Studio Potter with the recounting of several oral testimonies from different members of the Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes communities.)

Some of their stories have been passed down from elder relatives or acquaintances in the community who knew how to make utilitarian clay wares and some from others who were looting at the end of the 1950s through 1960s as a means of survival.

In order to dignify and honor those whose knowledge, directly and indirectly, positioned Mata Ortiz ceramics as some of the most beautiful objects in the world, we must acknowledge ALL contributions. Then we can more fully understand the birth and evolution of the Mata Ortiz phenomenon. A single story has never been enough to fully encompass our rich and complicated history.

End notes

- Apaches...: Fantasmas De La Sierra Madre, by Manuel Rojas and Rascón Banda Víctor Hugo, Third ed., Instituto Chihuahuense De La Cultura, 2016, pp. 237–258.

- Terrazas, Joaquín. La Guerra Contra Los Apaches. First ed., Centro Librero La Prensa, 1905. The diary of Colonel Jaoquin Terrazas. In his notes he also describes the meetings he and other officers from the Mexican army had together with Ju and Geronimo constantly luring them into peace agreements just in order to capture them, dead or alive.

- Ibid, Terrazas describes at the beginning of his diaries how the scalps had to be removed and collected in order to prove to the government the number of apaches that were killed.

- Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca, by Di Peso Charles C., Amerind Foundation, 1974, p. 20.

- Ibid.

Share

Share